The cost of knowledge graphs

There is interest and excitement building around the potential of knowledge graphs (“interlinked descriptions of entities [that] also encod[e] the semantics”) to drive content operations. I believe that knowledge graphs and content management systems (CMSs) that sit on top of knowledge graphs have a critical part to play, but I also have some concerns.

Since 2013, Scriptorium has had a very informal content maturity model:

- Crap on a page

- Design consistency

- Template-based content

- Structured content

- Content in a database

Each level is explained in Why is content strategy hard?

You need at least level 4 for efficient content ops, and many organizations need level 5. The basic difference between levels 4 and 5 is how you store the content. In theory, you can create structured content in text files (XML or other markup). In practice, a database gives you better insight into content relationships, which in turn makes it easier to deliver improved customer experience. Knowledge graphs are level 5.

Structured content is information that captures the relationships and requirements among content components. For example, an article must have an author and an author must include a bio. An article that doesn’t include an author is invalid or incomplete.

In modern digital content production, we have linear documents (like Word files). The only relationship is sequential—paragraph 1 comes before paragraph 2.

Content relationships are linear in word processing

The formatting of the document carries implied structure.

Formatting implies content structure

Structured content captures the implied structure explicitly. By adding containers like “section,” you can describe the relationships among the various document components with more precision. But structured content is still limited to sequence (up and down) and hierarchy (left and right). In effect, these documents are two-dimensional instead of linear.

Content relationships are hierarchical and sequential in structured content

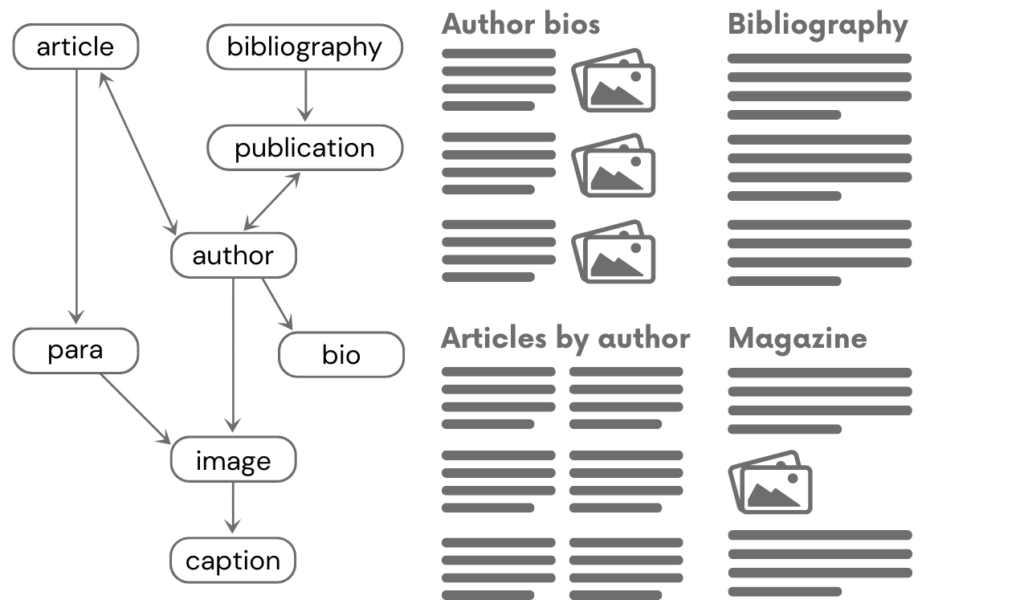

Content management systems (CMSs) capture these hierarchical and sequential structural relationships. Knowledge graphs take the next step. Instead of a tree structure, a knowledge graph provides for multidimensional relationships, where content objects are interwoven. To create a document, web page, or other publication, you use the knowledge graph relationships to extract the relevant information.

For example, consider the simplified example of an author. For an author, your knowledge might include a name, a biography, and a photo. You could use the name and photo in an article as a byline. The author’s name (but not bio or photo) might appear in a citation or a bibliography. And finally, you can create a page that lists all of a particular author’s publications based on the relationship between author and articles. The key here is that all of the necessary information is in the knowledge graph and you query the knowledge graph to extract the relevant connections and information.

Content relationships are multidimensional in knowledge graphs

Using knowledge graphs as a foundation for content delivery will be challenging. It has more in common with building web page dashboards or web interfaces than with documents.

We have to think about the various content or data objects, understand how they relate to each other at the knowledge graph level, and then bring them together into a coherent experience, whether a webpage, a document, or something else entirely.

We have struggled mightily with XML. Even in technical content, which has been historically the friendliest to structure, it’s estimated that, at best, 30% is structured. And note that this 30% is measured in surveys of professional technical writers. It almost certainly omits the huge amounts of content being created by people who are not identified as professional communicators. The vast majority of technical and product content is level 1 or 2 and stashed in Word, even when it is high-stakes technical content.

Knowledge graphs and headless CMSs are suddenly all the rage for websites and specifically marketing content. But looking at the content maturity model above, I foresee trouble ahead.

In the last 20 years or so, some technical content has made a painful transition from template-based content (level 3) to structured content (level 4). From structured content, it’s a relatively smaller step into knowledge graphs.

The situation for marketing content is different. Design systems provide guidance for content formatting, so a website driven by a design system is at level 2. Template-based authoring, or at least rigorous template-based authoring, is rare in marketing content. In many CMSs, there are templates or forms that guide authors, but the systems offer escape hatches—a way to insert arbitrary HTML and get around the requested framework.

Marketing teams are now facing requirements to increase velocity, scale localization, and deliver content across many different channels. For this, they will need structured content and a content management system that can feed all the needed channels. Moving up in the content maturity model is always challenging, and a jump across multiple levels is daunting. Trying to move from design-forward content (level 2) all the way to knowledge graphs (level 5) is truly terrifying.

To succeed, we need a mindset shift from “make it pretty” (level 2) to a recognition that consistently organized and structured content provides value by improving the customer experience and enabling innovation. The service providers and software vendors need to step up to provide the necessary system and services to help make the transition.

What do you think? Does your organization need to move up in the content maturity model? Do you need knowledge graphs?

Vinish Garg

I think the use case of KGs in content processes is a one-dimensional view. If we can build the bets for how KGs can help the product itself for usability or metrics or the experience itself, that should open new adjacent use cases in content strategy, quickly enough.

For example I saw this post about how Airbnb uses KGs for search: https://productx.substack.com/p/airbnb-case-study

If KGs become central to the product story itself, it only means better foundations. For example for the entire metadata strategy itself and which directly involves content strategists.

Larry Kunz

Hi, Sarah. Great article. I absolutely agree that structured content (with semantic tagging) is the surest way to go. But when you have a bunch of level-2 marketing content, might it be possible to achieve at least partial gains in the user experience by adding taxonomy-based metadata to each piece of content and moving the content into a CMS that can extract meaning from the metadata? Perhaps that would work as a short-term approach until the team becomes accustomed to creating structured, template-based content. What do you think?

Sarah O'Keefe

Hi Vinish, there is definitely a need for wider perspective, but the article was too long already!

Sarah O'Keefe

Hi Larry, yes. Any small steps you can take to enrich the content make sense to me. Thinking about metadata and taxonomy also helps move away from page and pixel focus and toward a more strategic view of content. That, in turn, will make it easier to move up the maturity model. Several people pointed out in the LinkedIn thread about this article (https://www.linkedin.com/posts/sarahokeefe_the-cost-of-knowledge-graphs-scriptorium-activity-7016392571283230720-zW8q?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop)

that structured content is not a prerequisite to knowledge graphs. I agree in principle, but I also think that jumping from design-first to knowledge graphs is….problematic.